Thoughts on the Universal Dependencies proposal for Japanese

The problem of the word as a linguistic unit

18 September 2016 (with some later modifications)

The following is a rather long and rambling rumination on the current implementation of Universal Dependencies for Japanese from a general linguistic point of view.

The orthographic word

The syntactic word

Grammatical Treatments of Japanese

Traditional Japanese treatment of agglutinative elements

Non-traditional approaches

Summing up

Rejecting the bunsetsu

Digression: Arguments against the bunsetsu

POS assignments

Other agglutinative languages

Introduction

Universal Dependencies (UD) is a Google-supported project that is attempting to develop a cross-linguistically consistent treebank annotation based on dependency structures.

The stated objective of UD is to facilitate "multilingual parser development, cross-lingual learning, and parsing research from a language typology perspective". This worthy goal does not have its roots in grand theorising. UD began life as practical exercise in computer-assisted parsing within existing grammatical frameworks. The current model evolved from the Stanford Dependencies, which were designed for English; it has since added and refined dependency relations to accommodate the grammatical structures of typologically different languages while cleaning up some of the "quirkier and more English-specific features of the original version". More changes can be expected as language-specific values are incorporated.

Achieving consistent annotations across languages presents a daunting challenge. It means coming up with an inventory of categories and guidelines -- part of speech (POS) tags, lexical and grammatical features, and grammatical relations -- capable of fitting many different language types. The reorientation from analyses tailored to specific languages to more generalised cross-linguistic categories inevitably results in greater abstraction, with attendant risks. One major problem is ensuring that UD is implemented on the basis of shared assumptions. Porting existing analyses to UD poses unexpected challenges, especially for languages with typologies and grammatical traditions that differ from Western European languages.

Japanese is an object illustration of the pitfalls involved. In two papers entitled 日本語 Universal Dependencies の試案 (2014) and Universal Dependencies for Japanese (2015), a group of Japanese researchers attempt to port Universal Dependencies to the Japanese language. The results appear at the UD Treebank for Japanese. The implementation suffers from defects that are mostly rooted in confusion in applying the concept of 'word'.

The UD guidelines on tokenisation state quite explicitly:

The universal dependency annotation is based on a lexicalist view of syntax, which means that dependency relations hold between words. Hence, morphological features are encoded as properties of words and there is no attempt at segmenting words into morphemes. However, it is important to note that the basic units of annotation are syntactic words (not phonological or orthographic words)...

The Basic Policy at the Introduction to the proposed Japanese implementation, the meaning and import of which will only become clear as we explore the proposal further, hints at the intention to modify this principle:

The Japanese language is written without spaces or other clear divisions to show word boundaries. We tend to define morphemic units smaller than the word unit in order to maintain unit uniformity. Therefore, when we define the morpheme unit as the Universal Dependency word unit, we have to annotate the compound word construction, as defined in the morphological layer of Japanese linguistics.

The message here is somewhat opaque as the assumptions and framework are unclear. However, the net result is that the segmentation and assignment of categories diverge considerably from both UD principles and from proposals for other languages.

The Word

The orthographic word

In English and other modern European languages, consciousness of the word is heavily influenced by the orthographic word as delimited by white spaces.

This is not the case with Japanese writing, which has its roots in China. Unlike English, but like Greek and Latin, Classical Chinese was written without word spacing. This was partly because Classical Chinese was mostly (although not completely) monosyllabic and monomorphemic in nature. Each character was, on the whole, equivalent to a single morpheme and a single word, hence the term 'logograph'. In contrast, modern Chinese has many multi-morphemic (i.e. multi-character) lexical units, known under the influence of Western grammar as 词 cí or 'words'. Despite acknowledgement of the existence of 'words', the character still has greater visibility and arguably greater relevance to the modern Chinese reader than the 词 cí.

The 'logographs' (or kanji) that the Japanese borrowed from Classical Chinese continue to occupy a dominant position in Japanese writing and, as in Chinese, are perceived as fundamental units of form and meaning. But Japanese writing came to diverge even further from the 'one character - one word' model of Classical Chinese than modern Chinese. The 'logographs' are not only used to write monosyllabic forms borrowed from Chinese, as well as multi-character words into which they combine (as in modern Chinese); they are also used to write polysyllabic native Japanese words.

In addition, the Japanese also devised two syllabaries, hiragana and katakana, to represent the sounds of their language, which came to be used as an adjunct to Chinese characters. In the modern written language, hiragana tend to represent both content words and grammatical elements while katakana have several functions, including the writing of words borrowed from Western languages. While they represent sounds rather than meanings, individual kana occupy the same unit of physical space on the page as Chinese characters.

The result is that modern Japanese writing involves an interplay between the 'logographic' kanji and 'phonetic' kana, tending to highlight the difference between 'content words' (nouns, verbs, adjectives, etc.), which have a tendency to be written in Chinese characters or katakana (although hiragana are also used), and 'empty words' (grammatical forms), which are mostly written in hiragana. While it thus corresponds to certain aspects of Japanese linguistic structure, this hybrid writing system is very flexible and refuses to be pinned down to word-like units. Although Japanese has now adopted Western-style punctuation, it has not adopted spacing between words (or word-like units), except in all-kana texts for children. This continues to militate against the development of a concept of discrete 'words' as found in European languages.

Alongside the traditional writing system, several romanisations have been developed to write Japanese in modern times. These conventionally separate words with white space and are largely uniform in the way they divide words. However, romanisation is not regarded as having the legitimacy of the traditional system and occupies only a peripheral or ancillary role in Japanese writing.

The syntactic word

Despite being a fundamental unit in Western grammar, the word has proved notoriously difficult to define. Its history as a linguistic unit in the West traces back to ancient Greek and Latin, which were inflected languages:

- Words changed form, usually by means of affixes, to indicate grammatical categories like case, gender, number, tense, person, mood, and voice.

- Word forms were organised into sets consisting of a base form (which linguists now call a 'lexeme') and inflected variants, arranged into matrices of abstract grammatical categories called 'paradigms'.

- Words played a central role in this model, which is known as the word and paradigm model.

As a simple example, the paradigm of the Latin noun LŪDUS 'game' is as follows. Each word has here been split into a stem and an ending, but they are normally written and understood as single units:

| LŪDUS | |||||

| Case | Singular | Plural | |||

| Nominative | lūd- | -us | lūd- | -ī | |

| Genitive | lūd- | -ī | lūd- | ōrum | |

| Dative | lūd- | -ō | lūd- | īs | |

| Accusative | lūd- | -um | lūd- | ōs | |

| Ablative | lūd- | -ō | lūd- | īs | |

| Vocative | lūd- | -e | lūd- | ī | |

- All forms shown are regarded as variants of the lexeme LŪDUS 'game', inflected for number and case.

- None of the specific endings can be directly equated to a grammatical category. For instance, there is no single element in the paradigm that consistently represents Plural or Dative. Conversely, the element -ī represents both Nominative Plural and Genitive Singular.

- It is not so much the endings themselves as their organisation into paradigms that gives inflections their meaning and function.

Verb conjugations are similar but more extensive and complex. For the verbal paradigm of Latin, see here or here.

- Some items in the paradigm, known as 'periphrastic forms', consist of two separate words. For example, the Perfective Passive form consists of a) the Perfect Passive Participle of the lexical verb plus b) the Present Tense of SUM 'to be'.

- The Perfective Passive of the verb LŪDŌ 'to play' is lūsus sum, where a) lūsus is the Perfective Passive Participle, b) sum is the First Person Singular Present Tense of the verb SUM. The meaning is 'I am mocked / teased / tricked'.

Latin grammarians drew a clear distinction between inflection, which concerns grammatical categories (person, number, tense, etc.), and derivation, which changes either the meaning or part of speech of the affected word. For instance, the noun LŪDUS 'game' is derived from the verb LŪDŌ 'to play' but is not an inflected form of the verb and has no place in its conjugation. It is a different word and is declined as a noun, as above.

English grammar traditionally follows the Greek and Latin model. For Anglo-Saxon, which was an inflectional language, the Greek/Latin model was a reasonable fit. But modern English has become a very different language from Anglo-Saxon:

- Almost all English nominal cases have been levelled. The only endings left are the Plural and the Possessive (Genitive). Accusative/Dative case is retained in vestigial form in personal pronouns (me, him, her, us, them) and the relative pronoun who (whom).

- Most conjugated verb forms are periphrastic. The only remaining inflections on the verb itself are Third Person Singular Present Tense (plays), Past Tense (played), Present Participle (playing), and Past Participle (played). The exception is the verb to be, which is still marked for Number and Person in the Present Tense (am, is, are) and Number in the Past Tense (was, were), and has a vestigial Subjunctive form (were).

Despite this, the concept of words taking different 'forms', and of derivation yielding different words, is retained in traditional English grammar.

The word in modern linguistics

In the 20th century the new discipline of linguistics shifted away from the word as the basic unit of grammatical description and adopted the morpheme as the 'smallest meaningful unit'. Rather than seeing played as the past tense form of the verb TO PLAY, linguists preferred to analyse it into two morphemes: the verbal root play, and the past tense morpheme -ed. Play is a free morpheme since it can occur independently; -ed is a bound morpheme since it can only ever appear bound to another element.

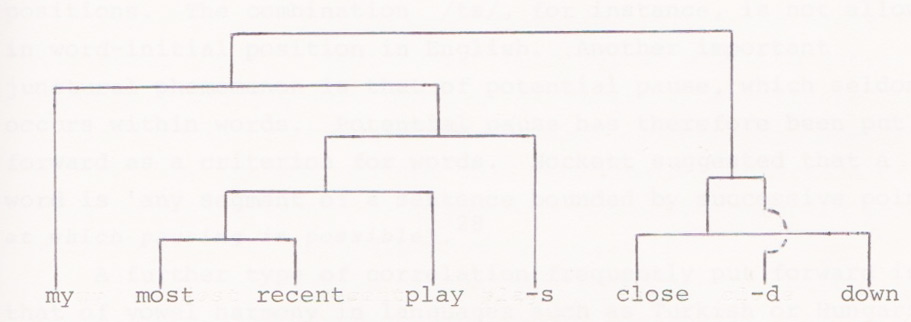

Some linguistic analyses proposed detaching inflectional endings from words altogether and attaching them to larger syntactic units. For example, Noam Chomsky's teacher, Zellig Harris proposed the following (rediagrammatised by R. H. Robins in immediate constituent or IC format):

In this analysis, the suffix -s attaches to the entire constituent most recent play and -d attaches to the constituent close down.

For most linguists, however, the adoption of the morpheme did not imply abandonment of the word. Instead, attempts were made to define the word in terms of rigorous criteria, especially in the light of the many new and typologically different languages, like those of the Americas, that were being described by linguists and anthropologists.

The most celebrated definition is Bloomfield's, which defined words as 'minimal free forms', that is, the smallest meaningful units of speech that can stand by themselves. Under this definition, play and played are both words because they can stand by themselves, while -ed is not a word because it cannot.

Linguists later fine-tuned the definition of words with further distributional criteria:

'Positional mobility (syntagmatic mobility)': the word is free to be used at different places in the sentence. For example, John will go can be transformed into Will John go?, indicating that will, John, and go are three separate words.

'Internal stability (internal immutability)': In contrast with the positional mobility that the word enjoys, morphemes within a word are fixed in order. For example, played is a stable unit that does not permit rearrangement as ed-play.

'Uninterruptability': it is not possible to insert anything between the morphemes of a word. For instance, it is not possible to insert anything between play and -ed (e.g., play-be-ed).

Whatever criteria are used, difficulties of interpretation and counterexamples can inevitably be found in different languages. Bloomfield himself noted that English the is not a 'minimal free form' because it is not uttered alone, except in citation form. He dealt with this by saying that the can be substituted with other forms, such as that, which are inarguably words according to his criterion. The other distributional criteria also have problems. For example, German separable verbs like abfahren 'to depart' fail to satisfy the criterion of uninterruptability since they can be separated into fährt ... ab 'departs' in actual use. Other exceptions have been found from other languages.

The Lexicalist Hypothesis

Early Transformational Grammar adopted a simple morpheme-centric approach to grammar. Derivational and inflectional morphology were both handled by the syntax. For example, processes like the derivation of the noun destruction from the verb destroy were handled by syntactic rules.

In 1970, Chomsky put forward what became known as the Lexicalist Hypothesis, arguing that nominal derivation should be handled in the Lexicon. Transformations (syntactic rules) should be reserved for regular and productive processes. Those that are not totally productive and transparent should be handled by the Lexicon. Transformations should not be used to insert, delete, permute, or substitute the subparts of words. The adoption of the Lexicalist Hypothesis represents the reinstatement of the word as a distinct level of representation in grammar.

The Lexicalist Hypothesis later developed two versions. The weak version holds that transformations (syntactic rules) cannot be used for derivational morphology; the strong version holds that this requirement should be extended to inflection.

The Nature of Japanese

Before going any further, we need to consider the word in Japanese in the light of the above.

The stated purpose of Universal Dependencies for Japanese is to port the UD annotation scheme to Japanese -- although it is more accurate to regard it as an attempt to convert native Japanese annotations to the UD format.

Stated simply, the problem with the UD annotation for Japanese is that it takes as its basis traditional Japanese grammar, a grammatical system that has developed its own peculiar grammatical analysis based on a very weak conception of the 'word'. It is essential to understand the larger background of Japanese in order to understand the UD Treebank for Japanese.

Japanese: an Agglutinating Language

Japanese is traditionally classed as an agglutinating language. In simple terms, this means that the key parts of speech -- content words like nouns, verbs, and adjectives -- are normally followed by strings of functional morphemes. As a group, I will call these functional morphemes 'agglutinative morphemes'.

For nouns, the process of agglutination mostly involves adding clitics known as particles in English and 助詞 joshi in Japanese to the dictionary form of the noun. The classification of particles is somewhat complex, with co-occurrence and ordering subject to rules and conditions. Some can be classed as case particles:

本が hon ga 'book (subject)'

noun 'book'

honnominative particle

ga

ご飯を go-han o 'meal (object)'

noun 'meal'

gohanaccusative particle

o

東京から tōkyō kara 'from Tokyo'

noun 'Tokyo'

tōkyōablative particle (from)

kara

友達の tomodachi no 'friend's'

noun 'friend'

tomodachigenitive particle ('s)

no

Others include 'focus particles' like は wa (indicates topic), も mo ('also'), こそ koso (emphatic), and the nominalising particle の no. Particles can occur in combination:

東京は tōkyō wa 'Tokyo (topic)'

noun 'Tokyo'

tōkyōtopic (as for)

wa

東京からは tōkyō kara wa 'as for from Tokyo...'

noun 'Tokyo'

tōkyōablative (from)

karatopic (as for)

wa

東京からも tōkyō kara mo 'also from Tokyo'

noun 'Tokyo'

tōkyōablative (from)

kara'also'

mo

東京からこそ tōkyō kara koso '(it's) precisely from Tokyo that...'

noun 'Tokyo'

tōkyōablative (from)

karafocus particle (emphatic)

koso

東京からの tōkyō kara no 'which is from Tokyo'

noun 'Tokyo'

tōkyōablative (from)

karagenitive particle ('s)

no

Overall, however, the number of particles that can follow a noun is not large, usually not more than three.

For verbs the process of agglutination is more elaborate. Verb stems are more closely integrated with the agglutinative morphemes (generally known as 助動詞 jodōshi, literally 'helping verbs') that follow them. Strings of morphemes are generally longer. The rules of ordering and attachment are more complex. There are gaps, exceptions, and part-of-speech switching.

Take the verb 遊ぶ asobu 'play'. The non-past form is 遊ぶ asobu:

遊ぶ asobu 'play'

verb stem 'play'

asob-non-past tense marker

-(r)u

The past tense is 遊んだ asonda 'played', made up of ason-, a bound form of the verb asobu, plus the voiced form of the past tense (strictly speaking, perfective) morpheme た ta:

遊んだ asonda 'played'

verb stem 'play'

ason-past tense marker

-da

遊んだ asonda is phonologically fused and the two constituent morphemes, ason- and -da, are never used on their own.

A verb stem can be followed by a number of agglutinative morphemes:

遊ばれた asobareta 'was played (with)'

verb stem 'play'

asob-passive

-(r)are-past tense marker

-ta

遊ばせられた asobaserareta 'was caused / allowed to play'

verb stem 'play'

asob-causative

-(s)ase-passive

-(r)are-past tense marker

-ta

遊ばせられました asobaseraremashita 'was caused / allowed to play (polite)'

verb stem 'play'

asob-causative

-(s)ase-passive

-(r)are-politeness marker

-mas-(i)-past tense marker

-ta

遊べる asoberu 'can play'

verb stem 'play'

asob-potential marker

-(r)epresent ending

-(r)u

遊べば asobeba 'if play'

verb stem 'play'

asob-conditional

-(r)eba

These agglutinative morphemes (affixes) are discrete forms with a clear function and meaning.

But there are wrinkles.

The string of morphemes following verbs may include forms (such as いる iru 'to be' and くれる kureru 'to give (towards speaker)'), both of which would be full verbs in any other context:

遊んでいる asondeiru 'is playing'

verb stem 'play'

ason-conjunction (or ending)

-deauxiliary verb 'to be'

i-present tense marker

-(r)u

遊んでくれます asondekuremasu 'play (as a favour to someone)'

verb stem 'play'

ason-conjunction (or ending)

-deauxiliary verb 'to give'

kure-politeness marker

-mas-present tense marker

-(r)u

遊ばせられていました asobaserareteimashita 'had been caused / allowed to play (polite)'

verb stem 'play'

asob-causative

-(s)ase-passive

-(r)are-conjunction (or ending)

-teauxiliary verb 'to be'

i-politeness marker

-mas-(i)-past tense marker

-ta

Strings of Japanese 'agglutinative morphemes' often cross (and re-cross) part-of-speech boundaries, notably the verb-adjective boundary. The most prominent example is the negative, which in non-polite forms is expressed by an adjectival:

遊ばない asobanai 'not play'

verb stem 'play'

asob-negative adjective

-(a)na-adjective ending

-i

遊ばなかった asobanakatta 'did not play'

verb stem 'play'

asob-negative adjective

-(a)na-adjective linking form

-kat-past tense marker

-ta(かっ -kat- is diachronically derived from くあっ -ku at-, where く -ku is an adjectival ending and あっ at- is a form of the verb ある aru 'to be'.)

遊ばなければ asobanakereba 'if not play'

verb stem 'play'

asob-negative adjective

-(a)na-adjective linking form

-ke-conditional

-(r)eba(けれ -kere- is diachronically derived from くあれ -ku are-, where く -ku is an adjectival ending and あれ are- is a form of the verb ある aru 'to be'.)

Other commonly used adjectival morphemes include たい -tai 'want to' and やすい -yasui 'easy to', and all can be extended with further morphemes (such as continuative くて -kute and past tense かった -katta) like any adjective.

遊びたい asobitai 'want to play'

verb stem 'play'

asob-i-'want to'

-ta-adjective ending

-i

遊びやすい asobiyasui 'easy to play'

verb stem 'play'

asob-i-'easy to'

-yasu-adjective ending

-i

If it follows the politeness marker ます -mas-, the negative is expressed by the form ん -n, as in 遊びません asobimasen 'not play (polite)', rather than the expected form *遊びまさない *asobimasanai. The polite past negative is expressed by the periphrastic form 遊びませんでした asobimasendeshita, not *遊びまさなかった *asobimasanakatta. Historically ん -n is an abbreviation of the negative form ぬ -nu, which does not allow further agglutinative morphemes to be added directly, thus breaking the regular negative pattern. The periphrastic polite past negative form is thus:

遊びませんでした asobimasendeshita 'did not play (polite)'

verb stem 'play'

asob-i-polite form

-mas-e-negative form

-npolite copula

des-i-past tense

-ta

The above does not exhaust the system of 'agglutinative morphemes' associated with Japanese verbs. We have only made passing mention of adjectival endings, which are not as easily segmentable as verbs due to the diachronic coalescence of forms, creating what are basically empty morphs like -kere- and -kat-. We have not discussed evidential forms (そう -sō, よう-yō, etc.), various other negative and imperative forms, or presumptive forms (う -u, よう -yō, etc.). Nor have we discussed the paradigm of honorific and humble forms that are so common in Japanese. We have not touched on forms like ながら -nagara 'while (doing)', つつ -tsutsu 'while (doing)', がてら -gatera 'while coincidentally doing', がち -gachi 'tend to', and がる -garu 'show outward signs of', which are generally not regarded as forming part of any kind of 'verbal conjugation' and are not regarded as verbal auxiliaries (助動詞 jodōshi). And we have not included nominalised forms (e.g., 遊ばないんであれば asobanain' de areba 'if not going to play'), which are ubiquitous in Japanese but are usually treated separately from the 'verbal conjugation'.

As can be appreciated from these examples, Japanese agglutinative morphemes are largely segmentable elements which have an identifiable form and function (although there are some 'empty' elements) and follow complex rules of ordering and combination. They differ from the endings in fusional languages, which, as we saw, are often difficult to map directly to individual grammatical categories. More importantly, the system of 'agglutinative morphemes' is not easily organised into a closed system like the paradigms of fusional or inflectional languages like Latin. This greatly complicates any attempt to organise and classify 'agglutinative morphemes', particularly those associated with verbs.

The Japanese system of 'agglutinative morphemes' also differs from English. For nouns, English has almost completely lost inflectional endings, while verbal inflectional marking is limited, with heavy use of periphrastic forms. As a result, English grammatical categories such as tense, voice, or aspect are often expressed through individual words rather than agglutinated or inflectional forms.

Since Japanese differs from both Latin and English, it is an interesting question how Japanese agglutinative morphemes are treated within Japanese grammar. The grammatical treatments that the Japanese have come up with for their language are somewhat different from the 'word and paradigm' system that grew out of Greek and Latin.

Grammatical treatments of Japanese

Grammatical studies of Japanese tend to be divided into two streams. One is that of linguistics (言語学 gengogaku), which is more in tune with various currents in the international discipline of linguistics, particularly as practised in Western countries. The other is kokugogaku (国語学, literally 'national language study'), an approach which can trace its roots back to the Edo period but is largely identified with analyses by scholars of the Taisho and Showa eras. One school of kokugogaku furnishes the basis of Japanese school grammar.

While the line between the two approaches is now increasingly blurred and there is considerable mixing, understanding the two is essential in grasping the roots of the implementation of UD in Japanese.

Traditional Japanese treatment of agglutinative elements

Modern-day ayui

Japanese grammarians of the eighteenth century had already noticed the agglutinating nature of their language. Borrowing from the vocabulary of dress and ornament, Fujitani Nariakira (1738–1779) described adverbs and connectives as 'hairpins' (挿頭 kazashi), and forms that followed nouns and verbs as 'binding cords' (脚結 ayui). It is the binding cords that embody the agglutinating nature of the language.

Grammatical studies of verbal conjugations (活用 katsuyō) and particles (テニヲハ te ni wo ha) were of particular concern to later nativist scholars, as exemplified in Kotoba no yachimata (詞八衢) by Motoori Haruniwa (本居春庭) published in 1808. Grammarians of this era originated the traditional approach to verb conjugations, which is still in use today. For example, the currently accepted conjugation of the yodan-class (四段 yodan) verb 遊ぶ asobu 'to play' in Classical Japanese is as follows:

Name English Root Ending 未然形 mizenkei 'irrealis' 遊 aso- ば -ba- 連用形 ren'yōkei 'conjunctive' 遊 aso- び -bi- 終止形 shūshikei 'predicative' 遊 aso- ぶ -bu 連体形 rentaikei 'adnominal' 遊 aso- ぶ -bu 已然形 izenkei 'realis' 遊 aso- べ -be- 命令形 meireikei 'imperative' 遊 aso- べ -be

This approach to verbal conjugation, combined with an analytical approach to 'agglutinative morphemes', has had an enduring influence on attempts to define the word in Japanese.

Kokugogaku

In the modernising era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, grammatical studies were advanced under the rubric of kokugogaku (国語学), influenced by Western grammar. The pioneer in this field was Ōtsuki Fumihiko (大槻文彦 1847-1928), but what are now considered the four main grammarians of kokugogaku were Yamada Yoshio (山田孝雄 1875-1958), Matsushita Saburō (松下三郎 1878-1935), Hashimoto Shinkichi (橋本進吉 1882-1945), and Tokieda Motoki (時枝誠記 1900-1967). Each grappled with parts of speech in Japanese, in particular the 'agglutinative morphemes' that are lacking in most European languages. Their efforts involved attempts to reconcile the 'words' of Western grammar with the realities of the Japanese language.

There was by no means unanimity of treatment or terminology among kokugogaku scholars. Looking just at verbal endings:

- Yamada (1908, 1922) regarded agglutinative morphemes after the verb as similar to affixes, calling them 'complex endings' (複語尾 fukugobi). He did not treat them as separate words because they cannot be used apart from the verb they are attached to, and cannot be separated from it by another word.

- Matsushita set up a unit called the 詞 shi, which he regarded as a 'word' in the Western sense. 詞 shi were combinations of 完辞 kanji (roughly 'complete words'), which were free morphemes, and 不完辞 fukanji (roughly 'incomplete words') which were what I am calling 'agglutinative morphemes'. Verb + ending(s) were thus regarded as single words.

- Hashimoto (1933) set up a unit called the 文節 bunsetsu, literally 'sentence segment', which he equated to Matsushita's 詞 shi. Hashimoto defined bunsetsu by phonological criteria of accent and pause. Syntactically, they were characterised as "individual parts that cannot be further divided as actual language" (実際の言語としてはそれ以上に分けることができない個々の部分 jissai no gengo to shite wa sore ijō ni wakeru koto ga dekinai ko-ko no bubun). This closely resembles Bloomfield's definition of the word as a 'minimal free form'.

Hashimoto then divided bunsetsu into 語 go ('words') or 単語 tango ('single words'). The terms 語 go and 単語 tango do not have a long history in Japanese. They appear to have originated among students of Western learning in the late Edo period. The earliest recorded use in the sense of 'word' was in the title of a glossary of French published in 1862, although the first mention in dictionaries was not until 1887. Hashimoto in this way incorporated the 'word', a concept imported from the West, into his grammatical theory.

Hashimoto captured the agglutinative nature of Japanese by classing 単語 tango into two types: 詞 shi (自立語 jiritsu-go 'autonomous words' or 'free words'), which can form bunsetsu by themselves, and 辞 ji (付属語 fuzoku-go 'dependent words' or 'bound words'), which can only form bunsetsu in combination with 詞 shi. To use a fairly simplistic characterisation, a bunsetsu typically consists of a free word (詞 shi) followed by one or more bound words (辞 ji).

Yamada's 複語尾 fukugobi 'complex endings', Matsushita's 不完辞 fukanji 'incomplete words', and Hashimoto's 辞 ji were all affixes to the verb, and all were regarded as non-independent forms.

Hashimoto then classed the 詞 shi and 辞 ji as follows:

1. 詞 shi were divided into two types: conjugable words (活用するもの katsuyō suru mono) and non-conjugable words (活用せぬもの katsuyō senu mono).

Conjugable words included verbs and adjectives. Hashimoto used the traditional concept of 活用 katsuyō for verb conjugations. Not all of the conjugated forms actually satisfy the critera for free forms.

Non-conjugable 詞 shi included nouns, pronouns, and numerals as well as adverbs and types of conjunction.

2. 辞 ji (literally 'dependent words') only occurred attached to other words. They were further divided into two types:

Conjugable 辞 ji were known as 助動詞 jodōshi 'verbal auxiliaries'. They included, but were not confined to:

The causative form: せ, させ -(sa)se-

The passive form: れ, られ -(ra)re-

The politeness marker: まし, ます, ませ -mas-

The past tense marker: た -ta.

The evidential marker: そう -sō.

The presumptive marker: う -u, よう -yō.

The 助動詞 jodōshi also included the copula だ da, which follows nouns and other parts of speech and is also conjugated. (Yamada treated だ da, です desu, etc. as verbs, and thus as free words.)Non-conjugable 辞 ji, known as 'auxiliary words' (助詞 joshi, usually called 'particles' in English), largely followed nouns, as in 本が hon ga 'book + nominative particle'.

Of interest here is that Hashimoto recognised both 詞 shi or 'free words' and 辞 ji or 'bound words' as belonging to the category of 語 go 'word'. For instance, 山 yama 'mountain' and 川 kawa 'river' were regarded as 語 go, as were the agglutinative passive morpheme (ら)れ (r)are and the past tense marker た ta.

On the other hand, morphemes that formed constituent parts of 詞 shi 'full words' were not regarded as 語 go. For example, 赤鬼 aka-oni 'red ogre' and はげ頭 hage-atama 'bald head' were regarded as individual 語 go, while the constituent components 赤 aka- 'red', 鬼 -oni 'ogre', はげ hage- 'bald', and 頭 -atama 'head' were regarded as sub-word units. This decision was made on both syntactic (they do not function as independent syntactic units in the sentence) and accentual (they do not have an independent accent contour) grounds.

The superficial beauty of Hashimoto's approach was the apparent symmetry between 'agglutinative forms' (辞 ji) following nouns and those following verbs. However, it achieved this by sweeping details under the carpet.

Hashimoto adopted the approach to verb conjugations found in the work of Motoori Haruniwa and other early grammarians, updated for the modern colloquial. For example, the conjugation of godan-class (五段 godan) verbs, often known in English as 'consonant-ending verbs' or 'consonant verbs', is as follows:

Name English Root Ending 未然形 mizenkei 'irrealis' 遊 aso- ば -ba-

ぼ -bo-連用形 ren'yōkei 'conjunctive' 遊 aso- び -bi 終止形 shūshikei 'predicative' 遊 aso- ぶ -bu 連体形 rentaikei 'adnominal' 遊 aso- ぶ -bu 仮定形 kateikei 'conditional' 遊 aso- べ -be- 命令形 meireikei 'imperative' 遊 aso- べ -be

The conjugated forms act as verb stems. Some are followed by 辞 ji ('agglutinative morphemes'), while others are able to stand on their own, e.g., the 終止形 shūshikei 'predicative', which ends a sentence. Some forms can function in both roles, such as 遊び asobi, which can stand on its own as a continuative form and can also be followed by 辞 ji, as in 遊びます asobimasu 'play (polite)'.

As result, three kinds of conjugated verb stem fell into the category of 語 go: 1) forms that can stand by themselves, 2) forms that can either stand by themselves or be followed by agglutinative morphemes, 3) forms that cannot stand by themselves and are obligatorily followed by agglutinative morphemes. The second type partly, and the third type clearly depart from Western concepts of the 'word'.

One important form lacking from the table is 遊ん ason-, found in combination with the past tense marker た -ta and the て -te ending, which is regarded as secondarily derived from the continuative form 遊び asobi via what is known as 'euphonic change' (音便 onbin).

With regard to 辞 ji attaching to verbs, Hashimoto admitted that there is no fundamental distinction between his 辞 ji and suffixes, merely a difference in degree. He described 辞 ji as attaching freely and regularly whereas suffixes attach according to 'customary usage'. Despite the lack of any fundamental distinction, he felt that 辞 ji differed from other suffixes, and for this reason agreed with Yamada's treatment of agglutinative morphemes after the verb as 'complex endings' rather than suffixes. However, unlike Yamada, who classed them as belonging to the preceding verb, Hashimoto decided that such 辞 ji should be treated as separate 語 go, although he also regarded them as subordinate to the larger unit of the bunsetsu. This fateful decision over 80 years ago, to class agglutinative forms following verbs as 'words', eventually led to the current treatment of both particles and verbal auxiliaries as separate words in Japanese grammar, and thus the current Japanese implementation of UD.

In later studies Hashimoto also developed the concept of 連文節 renbunsetsu 'linked bunsetsu' in analysing sentence structure. By combining bunsetsu into larger units on mostly semantic grounds, Hashimoto placed the bunsetsu at the centre of grammatical relations in Japanese.

Hashimoto's grammar was adopted for teaching in Japanese schools during the 1930s and has had the greatest influence on subsequent Japanese grammatical studies. It is now regarded within Japan as 'standard' and is used by institutions such as the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics (NINJAL: 国立国語研究所 kokuritsu kokugo kenkyūjo), for syntactic tree parsing, such as the Kyoto University Text Corpus (Kurohashi and Nagao, 2003), and for the output of syntactic parsers.

Examples of bunsetsu

Under Hashimoto's grammar, some of our earlier examples can be analysed as follows (bunsetsu are enclosed in dashed lines; free or 'autonomous' words are shown with thickened borders):

one bunsetsu, two words: independent word + case particle

本

honが

gaone bunsetsu, two words: independent word + case particle

ご飯

go-hanを

oone bunsetsu, three words: independent word + case particle + particle

東京

tōkyōから

karaは

waone bunsetsu, two words: independent word (conjunctive) + verbal auxiliary

遊ん

asonだ

daone bunsetsu, three words: independent word (irrealis) + verbal auxiliary (inflected) + verbal auxiliary

遊ば

asobaれ

reた

taone bunsetsu, four words: independent word (irrealis) + verbal auxiliary (inflected) + verbal auxiliary (inflected) + verbal auxiliary

遊ば

asobaせ

seられ

rareた

taone bunsetsu, five words: independent word (irrealis) + verbal auxiliary (inflected) + verbal auxiliary (inflected) + verbal auxiliary (inflected) + verbal auxiliary

遊ば

asobaせ

seられ

rareまし

masiた

tatwo bunsetsu, seven words: [independent word (irrealis) + verbal auxiliary (inflected) + verbal auxiliary (inflected) + conjunction particle (接続助詞 setsuzoku joshi)] + [independent word (auxiliary verb 補助動詞 hojo dōshi, conjunctive) + verbal auxiliary (inflected) + verbal auxiliary]

遊ば

asobaせ

seられ

rareて

teい

iまし

masiた

ta

Hashimoto vacillated over this form but it was eventually divided into two bunsetsu. The verb いる iru 'to be, exist', an auxiliary verb, is regarded as an independent word (詞 shi).

two bunsetsu, four words: [independent word (conjunctive) + conjunction particle (接続助詞 setsuzoku joshi)] + [independent word (auxiliary verb 補助動詞 hojo dōshi, conjunctive) + verbal auxiliary (inflected)]

遊ん

asonで

deくれ

kureます

masuone bunsetsu, two words: independent word (conditional) + conjunction

遊べ

asobeば

ba

For adjectival forms, such as the negative form of the verb:

one bunsetsu, two words: independent word (irrealis) + adjective

遊ば

asobaない

naione bunsetsu, three words: independent word (irrealis) + verbal auxiliary + verbal auxiliary

遊ば

asobaなかっ

nakatた

ta

The polite negative past form is as follows:

one bunsetsu, five words: independent word (conjunctive) + verbal auxiliary + verbal auxiliary + verbal auxiliary + verbal auxiliary

遊び

asobiませ

maseん

nでし

desiた

taAs noted previously, the copula form でし deshi- is treated as a verbal auxiliary (助動詞 jodōshi) by Hashimoto.

With regard to the potential form of the verb, 遊べる asoberu 'can play', in school grammar this is treated as a separate verb from 遊ぶ asobu and is known as the 'potential verb' 可能動詞 kanō-dōshi. The reason for this treatment is that it is historically an abbreviation of 遊ばれる asobareru and is found only in consonant-ending (godan) verbs, although it is now gradually spreading to verb-ending (ichidan) verbs.

Although there was no sudden break from earlier treatments, Hashimoto's decision to treat verb endings as 語 go had an important impact on Japanese grammatical standards.

Non-traditional approaches

While the school grammar treatment of 'agglutinative morphemes' based on Hashimoto is now widely accepted as standard within Japan, it has been questioned by linguists. One of the earliest was Hattori Shirō (服部四郎 1908-1995), who was one of Japan's most eminent linguists of international stature.

Hattori Shirō

Hattori was a student of Hashimoto's, but unlike most grammarians in the kokugogaku tradition he was open to European and American currents in linguistics, which at the time were mainly structuralist. He was familiar with a range of foreign languages including English, French, Russian, Turkish, Mongolian, and Chinese.

Hattori dealt with the status of 'agglutinative morphemes' in considerable detail in a number of papers, most notably in his 1950 paper 'Clitics and Bound Forms' (付属語と付属形式 fuzoku-go to fuzoku-keishiki). This paper put forward three principles for distinguishing between 'dependent words' (that is, clitics) and 'dependent forms' (that is, bound forms). Bound forms are affixes that attach to and form a part of other words. Clitics, on the other hand, are separate words, but have restricted independence and cannot stand as sentences on their own as required by Bloomfield's definition ('minimal free form').

(In linguistics, the clitic is regarded as lying midway between independent words and affixes, having the syntactic characteristics of a word but being phonologically dependent on another word or phrase. In English, the mobile genitive 's in expressions like the man you saw yesterday's wife is described as a clitic -- as a genitive it would normally attach to the noun man and not the entire expression the man you saw yesterday. However, linguists have disputed the fundamental nature of clitics and the term 'clitic' has been described as an umbrella term rather than a true grammatical category.)

Hattori's principles for distinguishing clitics (free forms) and bound forms were:

1. Those forms which can be attached to various independent forms differing in function or inflection are free forms (i.e., clitics).

2. Where a word can freely appear between two forms, the two forms are free forms. A form about which there is some doubt is a clitic.

3. If two linked forms can be transposed, they are both free forms.

Hattori's criteria differ slightly from the linguistic criteria considered earlier ('minimal free form', 'positional mobility', 'internal stability', 'uninterruptability') in adopting as their first principle the criterion of 'versatility of attachment'. It appears that this principle was specifically adopted to deal with the status of particles (助詞 joshi).

Hattori's treatment of particles

By the first principle, Hattori defined particles such as が ga, を o, は wa, etc. as clitics, that is, separate words. As noted earlier, particles following nouns fall into more than one type. が ga, を o, へ e, の no, etc. can be regarded as case particles, and as such are very closely linked to their preceding nouns. Being virtually inseparable from the noun, they are potentially treated as inflectional endings:

本が hon ga 'book + nominative particle'

ご飯を go-han o 'meal + accusative particle'

東京から tōkyō kara 'Tokyo + ablative particle ('from')'

本屋へ hon'ya e 'bookshop + allative particle ('to')'

友達の tomodachi no 'friend + genitive particle ('of')'

Hattori rejected this interpretation on the basis that such case particles attach not only to nouns but also to other particles and other parts of speech, and even embedded sentences. Taking the accusative particle を o as an example:

本を hon o 'book (obj.)'

子供のを kodomo no o 'the child's, that belonging to the child (obj.)'

私だけを watashi dake o 'just me (obj.)'

あるかないかを aru ka nai ka o '(the question) whether there is or not (obj.)'

Other kinds of particle show even greater freedom. Focus particles like は wa 'topic marker' and も mo 'also' can be found in various positions, including after verbs, other particles, nominalised verbs, and other parts of speech:

友達も tomodachi mo 'friend + focus particle ('also')' = 'friend also'

東京からも tōkyō kara mo 'Tokyo + ablative particle + focus particle ('also')' = 'also from Tokyo'

食べても tabete mo 'eat' + focus particle ('also')' = 'even if eat'

見てはいない mite wa inai 'see + focus particle (topic) + auxiliary verb + negative' = 'not looking (emphatic)'

行くのは iku no wa 'go + nominalising particle + focus particle (topic)' = 'to go (topic)' or 'the one that goes'

今は ima wa 'now + topic'

According to Hattori's first criterion, freedom of placement indicates that case particles, focus particles, and other kinds of particle (助詞 joshi) such as sentence-final particles (よ yo, ね ne, etc.) are clitics (free forms) rather than bound forms (inflections or endings).

Hattori's third criterion, transposability, also stipulates that particles like だけ dake 'only' and に ni 'to' must be recognised as clitics since both 私にだけ watashi ni dake 'to me only' and 私だけに watashi dake ni 'only to me' are possible orders.

Hattori noted that the semantic scope covered by particles can extend to sequences longer than words. For instance, the particle に ni 'to' and the object particle を o in the following sentences are both semantically attached not to 牛 ushi 'cow', but to 馬と牛 uma to ushi 'horse and cow':

馬と牛にやった

uma to ushi ni yatta

'gave to horse(s) and cow(s)'馬と牛を飼っている

uma to ushi o katte iru

'is/am/are raising horse(s) and cow(s)'

However, he rejected such semantic grounds for classing に ni and を o as clitics, citing the example of Tatar (Kazan), where the forms that correspond to に ni and を o are clearly bound forms (affixes), but resemble Japanese in attaching only to the second noun in the series:

at belæn sɨjərɣa birdem

literally 'horse and cow-to gave (1st person)'

'I gave to horse and cow'at belæn sɨjərnə aʃata

literally 'horse and cow (object) keeps (3rd person)'

'he is keeping horse and cow'

ɣa is equivalent to に ni and nə is equivalent to を o, but each is clearly an affix according to Hattori's three principles.

Hattori's treatment of verbal auxiliaries

Hattori's first criterion mostly defines agglutinative morphemes that attach after verbs as bound forms. These include verbal auxiliaries such as -(sa)se-, -(ra)re-, and -nai (attaching only to the 未然形 mizenkei), -mas- and -ta (attaching only to the 連用形 renyōkei), and -ba (attaching only to the 仮定形 kateikei), as well as conjunctions like -te (attaching only to the 連用形 renyōkei). These forms are not clitics since they do not attach to free forms.

The -te in 起きて okite and して shite look like clitics, being attached to the apparently free forms 起き oki- and し shi-. However, a comparison with godan conjugation (consonant verb) forms like 遊んで ason-de (from the verb 遊ぶ asobu) and 切って kit-te (from the verb 切る kiru 'to cut') show that the verb stem is what he called a 'pseudo free form' and -te is therefore an affix. Similarly, the -nai in both 遊ばない asobanai 'not play' and 起きない okinai 'not get up' is an affix, not a clitic.

The second principle shows that, unlike the -nai after verbs, the nai (negative) after adjectives is a clitic. The reason is that nai after an adjective can be separated by a particle, as in 白くはない shiroku wa nai 'not white', which is not possible with the negative of the verb (e.g., * 遊ばはない *asoba wa nai 'not play').

(Note that Hattori's principle is backed up by the different polite negative forms of the verb and adjective. Unlike ない -nai attaching to the verb, which attaches directly to the verb, ない nai attaching to the adjective is actually the negative form of the verb ある aru 'to be'. Thus 遊びません asobimasen 'do not play' vs 白くありません shiroku arimasen 'is not white'.)

Four major consequences of Hattori's criteria are:

1. Particles (助詞 joshi) are clitics. This matches their treatment in school grammar.

2. Verbal auxiliaries (助動詞 jodōshi) after verbs are suffixes, not clitics. This differs from the treatment in school grammar.

3. Negative ない -nai after verbs is a suffix. Negative ない nai after adjectives is a clitic.

4. The copula です desu / だ da is regarded as a separate word.

Hattori did recognise different degrees of cohesion among verbal agglutinative morphemes. ます -masu is more independent than たい -tai for accentual reasons, and たい -tai is more independent than ない -nai because it can attach to a potentially free form.

Later linguists

School grammar was also subjected to criticism from other Japanese linguists, including Sakuma Kanae (佐久間鼎 1888-1970), Suzuki Shigeyuki (鈴木重幸 1930-2015), Okuda Yasuo (奥田靖雄 1919-2002), Mikami Akira (三上章 1903-1971), and others. One of the key criticisms concerned the treatment of verbal auxiliaries (助動詞 jodōshi) as words. Linguists argued that they should be treated as suffixes or verb endings. (See Wikipedia 学校文法).

Operating outside the Japanese tradition, the American structuralist linguist, Bernard Bloch, used pause as a criterion to define words, supplemented by IC analysis (Bloch 1946). For example, in the construction あの建物へ ano tatemono e 'to that building', given that ano 'that' and tatemono 'building' had already been defined as words, Bloch used the IC analysis ano tatemono / e to define the particle へ e as a word. The overall result was that Bloch regarded agglutinative morphemes after nouns as separate words, while he treated agglutinative morphemes after verbs in a more complex fashion. Some forms he treated as derivational suffixes or inflectional endings, while he treated others as separate words.

Eleanor Harz Jorden abandoned Bloch's phonological criteria and adopted IC analysis alone to define words in Japanese, but arrived at similar results to Bloch.

The Japanese linguist Miyaji Hiroshi (1969) used distributional criteria to define particles as words, and verbal auxiliaries as constituents of words. However, he also regarded ます masu, まい mai, たい tai, and な na (prohibition) as separate words since they attach to potentially free forms.

John Chew (1964), analysing Japanese within a pre-lexicalist version of transformational grammar, doubted the applicability of the 'word' in Western grammar to Japanese and dealt only with phonological words (essentially equivalent to the bunsetsu).

Holistic approach

Most criteria for defining words betray a structuralist concern with objective, universally applicable tests (often known as 'discovery procedures') yielding black-and-white results. But the existence of 'words', or at least of fixed or stable strings of morphemes, can also be demonstrated more holistically.

In the case of agglutinative morphemes following nouns (particles or 助詞 joshi), Hattori's principle of 'versatility of attachment' captures the relative freedom that these forms enjoy.

In the case of verbs, a holistic approach is able to give greater structure to the simple, minimally differentiated string of 'agglutinative morphemes' posited by school grammar, which draws its main distinction between verbal auxiliaries (助動詞 jodōshi) and particles (助詞 joshi).

For example, school grammar treats て -te (the continuative form) as a conjunctive particle (接続助詞 setsuzoku joshi) and た -ta (past tense) as a verbal auxiliary (助動詞 jodōshi). This misses the fact that て -te and た -ta both have a clear terminating function within a string of agglutinative morphemes; that is, they both serve to terminate fixed sequences, and these fixed sequences in turn play a relatively flexible syntactic role within the sentence.

In distributional terms, た -ta occurs at the end of sentences and adnominal clauses, before nominalising particles, before conjunctions, and in certain other environments. For example,

Sentence final:

よく遊んだ yoku asonda

'(I) had a good time'Adnominal:

遊んだ人 asonda hito

'a person who played'Before a conjunction:

遊んだから asonda kara

'because (someone) played'Before a nominalisation:

遊んだのが asonda no ga

'the fact that (someone) played' / 'the one who played'

This is a similar syntactic environment to that of non-past verb forms. Asonda in the above structures can largely be substituted with the present-tense form asobu.

Forms ending in て -te occur at the end of clauses as a continuative form, before auxiliary verbs like いる iru 'to be', くれる kureru 'to give (towards hearer or speaker), しまう shimau 'to finish', and おく oku 'to place', and in requests. Particles like は wa (topic) and も mo ('also') can be placed after て -te, whether at the end of clauses or before auxiliary verbs.

This indicates that strings like 遊んだ asonda, 遊んで asonde, 遊ばせられた asobaserareta, and 遊ばせられて asobaserarete are usefully regarded as single units with a fixed internal structure but external syntactic flexibility. Grammatically, organising 遊んでいる asonde iru 'am playing' and 遊ばれていました asobarete imashita 'was being played with' into separate words -- the て -te form of the verb plus a form of the auxiliary verb いる iru -- neatly captures the progressive construction. Treating て -te as a conjunction, on the other hand, is less satisfactory in describing either the progressive aspect of the verb or other "-te plus auxiliary verb" constructions.

Another verbal auxiliary with a terminating function is conditional ば -ba. This form can occur at the end of clauses and, at times, before の no.

遊べばいい asobeba ii

'good if (you) play' = 'should play / go ahead and play'遊ばればの話 asobareba no hanashi

'talk of if be played' = 'assuming that (someone) was played'

Yet another verbal auxiliary with a terminating function is the negative ん -n in ません -masen. By terminating the verb form, ん -n forces the use of the periphrastic ませんでした -masen deshita sequence to express the polite past negative of the verb.

However, although useful for giving structure to the string of morphemes after verbs, such a 'holistic' approach will not always yield consistent or clearcut results. This is as it should be. It reflects the reality, noted by Hattori, that agglutinating morphemes in Japanese show varying degrees of independence.

Implications for verb paradigms

The traditional or school grammar approach to conjugation is based on the conjugation of verb stems, under the label of 活用 katsuyō. Different concepts of the word lead to different approaches to verb conjugation.

Hanada Yasunori (花田康紀) sets out the history and problems of the treatment of the verb in kokugogaku in detail in his 1984 paper 'Regarding the description of Japanese verbs - school grammar and what can replace it' (日本語動詞の記述をめぐって ー 学校文法とそれにかわるもの Nihongo dōshi no kijutsu o megutte - gakkō bunpō to sore ni kawaru mono). Problems with the traditional approach are interrelated and include 1) issues relating to the status of forms as words, 2) choice of categories to include in conjugations, and 3) the systematic treatment of verb roots and their suffixes.

An early verb conjugation outside the kokugogaku tradition was arrived at by Bernard Bloch in 1946. If we take 遊ぶ asobu as an example, Bloch set up the following conjugation (here slightly modified to incorporate improvements by later linguists). He regarded 遊ぶ asobu as having two bases: the long base asob- and the short base ason-. The Japanese names for verb forms are from Suzuki Shigeyuki.

Form Base Ending Base used Indicative (すぎさらず) asob- -u Long base Presumptive (さそいかけ) asob- -ō Imperative (命令) asob- -e Provisional (条件) asob- -eba Infinitive (第一なかどめ) asob- -i Past Indicative (すぎさり) ason- -da Short base Conditional (条件) ason- -dara Alternative (ならべたて) ason- -dari Gerund (第二なかどめ) ason- -de

Bloch's conjugational paradigm consists of a matrix of independent words, unlike the traditional approach, which posits a matrix of both free and bound verb stems.

Bloch's conjugation is tightly constrained, focussing on a subset of the range of forms associated with verbs. It deals only with plain (non-polite) forms and does not include evidential forms such as 遊びそう asobisō 'looks like playing' or adjectival forms such as the desiderative 遊びたい asobitai 'want to play'. He treats passive and causative forms (such as -(s)ase and -(r)are) as a product of derivation rather than inflection.

Suzuki Shigeyuki adopted Bloch's conjugation for Japanese verbs, along with the division between inflection (as shown in the above paradigm) and derivation. Suzuki posited the following as derivational rather than inflectional forms:

Form Base Endings うちけし (Negative) asob- -ana- -i うけみ (Passive) asob- -are- -ru つがいだて (Causative) asob- -ase- -ru ていねい (Polite) asob- -i-mas- -u ていねい命令 (Polite Imperative) asob- i-nasai うちけしの命令 (Negative Imperative) asob- -u-na できるたちば (Potential) asob- -e- -ru

This approach to conjugation, grounded as it is in a firmer concept of the word, is a step towards a clearer treatment of the agglutinative morphemes following verbs.

Implications for romanisation

I have refrained from raising the romanisation of Japanese since, as I mentioned, it is mostly regarded as peripheral by native speakers. However, it is notable that word divisions in the romanisation of Japanese mostly accord with Hattori's criteria rather than with those of school grammar. In particular, most romanisations:

1) do leave spaces between particles and preceding nouns. That is, they write hon ga ('book' + nominative) rather than honga.

2) do not leave spaces between verbal auxiliaries and verbs or other verbal auxiliaries. That is, asonda ('play' + past tense), not ason da; asobaseraru ('play' + causative + passive present), not asoba se rareru.

3) do separate the negative nai after adjectives, but not after verbs. That is, asobanai ('play + not'), not asoba nai; but shiroku nai ('white not'), not shirokunai.

4) do separate the copula. That is, sensei da ('teacher' + copula) not senseida; shizuka da ('quiet' + copula), not shizukada.

The reason for the clearer differentiation of word forms is, of course, partly due to the general practice in languages using the Latin alphabet of dividing text with white spaces. The old practice of scripta continua in Latin and Greek is no longer regarded as acceptable for writing with this alphabet.

Summing up

To sum up:

- The word is not a clear orthographic unit in Japanese for historical reasons.

- Japanese is an agglutinative language in which, for the most part, independent units (or words) are followed by grammatical units ('agglutinative morphemes') of varying degrees of independence. Unlike inflectional endings in inflectional languages, such 'agglutinative morphemes' are discrete units with clearly assignable grammatical functions.

- Very early native grammatical studies focussed on 'full words' (including conjugated verb stems) and the 'agglutinative morphemes' that follow them.

- Modern grammarians from the first half of the 20th century followed this tradition but disagreed on how the imported concept of the word should be applied to Japanese. Major points of difficulty were the treatment of agglutinative morphemes following verbs, which were generally agreed to be suffix-like in nature, and the treatment of the copula, which was regarded by some as an independent form.

- Hashimoto Shinkichi decided to treat agglutinative morphemes uniformly as dependent words (語 go). This included suffix-like forms that followed verbs, and the copula. Hashimoto regarded dependent words as combining with independent words into phonologically defined strings known as bunsetsu.

- Hashimoto's grammar was adopted for school grammar in the 1930s and thus passed into grammatical orthodoxy.

- Hashimoto's treatment has since been repeatedly disputed by linguists. In particular, the treatment of verb stems and verbal auxiliaries (助動詞 jodōshi) as 'words' has been criticised as linguistically incorrect.

- Alternative grammatical treatments under which strings of morphemes are structured into word units have been proposed and possess advantages for grammatical description. Such treatments are used in romanisations of Japanese.

- Despite this, orthodoxy has persisted due to its entrenched position in school grammar and is still used in the parsing of texts for linguistic analysis.

UD treatment of Japanese

As mentioned above, school grammar forms the basis for parsing and natural language processing studies by institutions such as the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics. To be sure, parsing frameworks and studies can and do modify school grammar in specific ways. For example, UniDic adopts novel POS such as 'adnominal' (連体詞 rentaishi) and modifies conjugations to classify 遊ぼう asabō 'let's play' as a separate verb form, the 意志推量形 ishisuiryō-kei 'intention conjecture form'. But the essential framework remains that provided by Hashimoto-based school grammar.

These parsing and NLP analyses, in turn, form the basis for the proposed UD implementation for Japanese.

Rejecting the bunsetsu

While it is based on existing NLP analyses, the UD implementation as currently proposed incorporates one particularly radical modification of the school-grammar model: it rejects the bunsetsu as the basic unit for Japanese syntactic tree parsing and adopts the 語 go in its stead.

This represents a fundamental repositioning of the 語 go. While Hashimoto treated 'agglutinative morphemes' as separate units, he also regarded them as dependent in nature, attaching to independent words to create larger syntactic units (bunsetsu). In particular, he recognised 'agglutinative morphemes' (辞 ji) following verbs as fundamentally no different from suffixes. By recognising them as independent words, the UD implementation goes far beyond what Hashimoto envisioned.

The decision to abandon the bunsetsu results in two major departures from UD principles:

- The UD implementation of Japanese treats all 語 go, whether independent or not, as independent units, and equates them to the 'word' as found in other languages.

- As supposedly independent words, such units are then assigned POS.

This new approach yields very different results in parsing, as can be seen if we restate some of our earlier examples in terms of the UD implementation. (Note that some analyses are based on educated guesses as not all forms are mentioned in the documentation.)

two words: NOUN + ADP [noun + adposition]

NOUN

本

honADP

が

ga

two words: NOUN + ADP [noun + adposition]

NOUN

ご飯

go-hanADP

を

o

three words: PROPN + ADP + ADP [proper noun + adposition + adposition]

PROPN

東京

tōkyōADP

から

karaADP

は

wa

two words: VERB + AUX [verb + auxiliary verb]

VERB

遊ん

asonAUX

だ

da

three words: VERB + AUX + AUX [verb + auxiliary verb + auxiliary verb]

VERB

遊ば

asobaAUX

れ

reAUX

た

ta

four words: VERB + AUX + AUX + AUX [verb + auxiliary verb + auxiliary verb + auxiliary verb]

VERB

遊ば

asobaAUX

せ

seAUX

られ

rareAUX

た

ta

five words: VERB + AUX + AUX + AUX + AUX [verb + auxiliary verb + auxiliary verb + auxiliary verb + auxiliary verb]

VERB

遊ば

asobaAUX

せ

seAUX

られ

rareAUX

まし

masiAUX

た

ta

seven words: VERB + AUX + AUX + CONJ + AUX + AUX + AUX [verb + auxiliary verb + auxiliary verb + conjunction + auxiliary verb + auxiliary verb + auxiliary verb]

VERB

遊ば

asobaAUX

せ

seAUX

られ

rareCONJ

て

teAUX

い

iAUX

まし

masiAUX

た

ta

two words: VERB + CONJ [verb + coordinating conjunction]

VERB

遊べ

asobeCONJ

ば

ba

For adjectival forms, such as the negative form of the verb:

two words: VERB + AUX [verb + auxiliary verb]

VERB

遊ば

asobaAUX

ない

nai

three words: VERB + AUX + AUX [verb + auxiliary verb + auxiliary verb]

VERB

遊ば

asobaAUX

なかっ

nakatAUX

た

ta

The polite past negative periphrastic form:

five words: VERB + AUX + AUX + AUX + AUX [verb + auxiliary verb + auxiliary verb + auxiliary verb + auxiliary verb]

VERB

遊び

asobiAUX

ませ

maseAUX

ん

nAUX

でし

desiAUX

た

taThe examples speak for themselves, but some of the peculiarities of this approach bear pointing out:

1. Many morphemes that would never be regarded as 'words' under any definition are treated as words in Japanese, with some extreme examples being 遊ん ason, ん n, い i, and なかっ nakat.

2. Heavily constrained sequences of bound morphemes, notably sequences of AUX, are interpreted as being made up of separate words. That is, stable sequences that would normally be regarded as word-internal are treated as being part of the syntax of the sentence.

3. Most of the so-called AUX (auxiliary verbs) are not syntactically verbs, therefore departing from the definition of 'auxiliary verb' given at the UD website.

4. Some of the resulting POS sequences are syntactically peculiar. For example:

The periphrastic verb form 遊びませんでした asobimasen deshita is analysed as a simple VERB + AUX + AUX + AUX + AUX string, rather than a combination of the Polite Negative of the verb plus the Polite Past of the copula.

The Polite Present Progressive verb form, "VERB + ています" (VERB + -te imasu), is analysed as VERB + CONJ + AUX + AUX. This involves using a coordinating conjunction to connect the verb stem (a bound form) with several auxiliary verbs (also bound forms).

The justification for abandoning the bunsetsu in the NLP literature is murky. In Tanaka et al (2015) it is dismissed almost in passing. The bunsetsu and 'agglutinative morphemes' are ignored due to an almost single-minded concentration on content words, particularly nouns.

Adopting the SUW

In implementing UD for Japanese, Tanaka et al (2015) adopt lexemes and the POS tagset as defined in the UniDic. This involves adopting the "short unit word" (SUW), corresponding to an entry conveying morphological information in the UniDic. This concern for the word as found in the lexicon (the lexeme) leads to a serious neglect of the 'agglutinative morphemes' that play such an important role in Japanese syntax.

The focus on the lexeme dates back to earlier papers in NLP, in particular the Balanced Corpus of Contemporary Written Japanese (BCCW) (Maekawa et al 2014), which adopts the SUW because of lexical issues with noun strings, particularly strings of Sino-Japanese nouns. Such strings pose a problem for the lexicon because they are highly productive, with a large number of potential combinations. For instance, lexical sources such as Juman, Yahoo!, IPA, and UniDi variously divide the string 国立国会図書館 kokuritsu kokkai toshokan 'National Diet Library' into 国立 + 国会 + 図書 + 館 kokuritsu kokkai tosho kan 'national + Diet + books + hall', 国立国会図書館 kokuritsukokkaitoshokan 'nationalDietlibrary', and 国立 + 国会図書館 kokuritsu kokkaitoshokan 'national + Dietlibrary'.

Maekawa et al therefore decide to analyse 国立国会図書館 kokuritsu kokkai toshokan 'National Diet Library' as a string of four SUW: 国立 + 国会 + 図書 + 館 kokuritsu kokkai tosho kan 'national + Diet + books + hall'. At a higher level, these are combined into a single LUW ("long-unit word") as 国立国会図書館 kokuritsukokkaitoshokan 'National Diet Library'. This allows the parser to interpret such strings without listing every possible combination in the dictionary.

Tanaka et al (2015) similarly propose combining SUWs, which they recognise may be too short for assigning syntactic relations and functions, into LUW. This is the background to the otherwise enigmatic passage quoted earlier: "We tend to define morphemic units smaller than the word unit in order to maintain unit uniformity. Therefore, when we define the morpheme unit as the Universal Dependency word unit, we have to annotate the compound word construction, as defined in the morphological layer of Japanese linguistics."

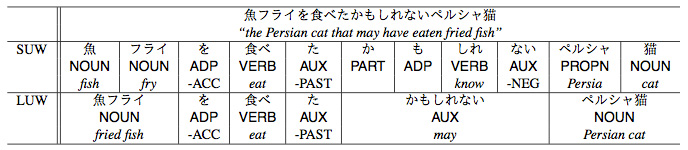

This process of combining SUW into LUW can be seen in the following sentence:

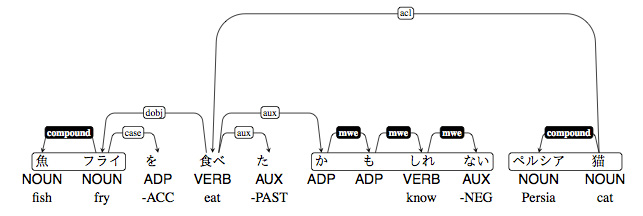

While UniDic lists 魚 sakana 'fish' and フライ furai 'fry' as separate SUW, the UD implementation combines these into the LUW 魚フライ sakana-furai 'fish fry' through the use of the compound tag. Similarly, the string of SUWs か も しれない ka mo shirenai, literally 'not know perhaps even', is combined into an LUW or functional phrase meaning 'may' through the use of the mwe (multi-word expression) tag. The resulting dependency tree is as follows:

While Tanaka et al (2015) note that the LUW "refers to the composition of bunsetsu units", the examples of LUW given appear to have no relation to the bunsetsu. The paper makes virtually no further mention of the bunsetsu as a syntactic unit. The bunsetsu, and the agglutinative morphemes that form an essential part of it, are simply ignored.

Digression: Arguments against the bunsetsu

Since papers by Tanaka et al (2014 and 2015) give no reason for rejecting the bunsetsu, it is necessary to search through some of their references in order to understand the background to this decision.

Arguments advanced against the bunsetsu can be divided into several types:

1) vague assertions that the 語 go, identified with the word in other languages, is more appropriate than the bunsetsu in parsing Japanese;

2) low-level procedural issues;

3) arguments of logic and grammar.

Vague assertions

At least two papers present vague, unsupported assertions as grounds for abandoning the bunsetsu.

One is Constructing a Practical Constituent Parser from a Japanese Treebank with Function Labels (Tanaka and Nagata 2013). The paper maintains that bunsetsu-based representations:

have serious shortcomings for dealing with Japanese sentence hierarchy. The internal structure of a bunsetsu has strong morphotactic constraints in contrast to flexible bunsetsu order. A Japanese predicate bunsetsu consists of a main verb followed by a sequence of auxiliary verbs and sentence final particles. There is an almost one-dimensional order in the verbal constituents, which reflects the basic hierarchy of the Japanese sentence structure including voice, tense, aspect and modality. Bunsetsu-based representation cannot provide the linguistic structure that reflects the basic sentence hierarchy.

The passage is making the impressionistic claim that internally rigid, syntactically flexible units are undesirable for parsing since their internal ordering corresponds to the "basic sentence hierarchy". No specific arguments are advanced in support of such a "basic sentence hierarchy", or for breaking up rigidly-ordered strings of bound forms for the purpose of parsing. It is possible that Tanaka and Nagata feel that the agglutinative grammatical forms of Japanese are equivalent to the independent grammatical forms of English, such as auxiliary verbs like be, have, must, will, etc. But without clear, firmly-based linguistic arguments, it is impossible to evaluate the paper's assertions. Given, however, that internal rigidity and external syntactic flexibility are the hallmarks of 'wordness', the comments appear to run counter to the Lexicalist Hypothesis and are difficult to reconcile with the fundamental principles of UD dependencies.

Another paper rejecting the bunsetsu is A Japanese Word Dependency Corpus (Mori et al 2013), referred to in Tanaka et al (2014), in which it is stated that:

For Japanese there is a dependency corpus.... Its unit is, however, phrase called bunsetsu, which consists of one or more content words and zero or more function words. This Japanese specific unit is not compatible with the word unit in other languages.

Mori et al go on to state that:

For the dependency annotation unit, we have chosen the word as in many languages. As we noted in the previous section, a language specific unit called bunsetsu is famous for Japanese dependency description.... This unit is, however, too long for various applications. In fact in some languages, a sentence is separated into phrases by white spaces when it is written. But phrases are divided into some smaller units in many researches.... [Footnote: In many researches on these languages, these phrases are called word because of they are visually similar to English word but they are phrase in granularity of meaning.] From the above observation, we decided to take word as the unit of our dependency corpus.

The passage makes several unsupported claims:

- The bunsetsu is a "language specific unit", that is, found only in Japanese, and is "not compatible with the word unit in other languages".

- The bunsetsu is too long for various applications.

- In some languages, white spaces divide written sentences into phrases, not words, requiring them to be divided into smaller units. (This appears to be adduced in support of the claim that the bunsetsu should be split up).

- The 'word' as found in other languages is adopted as the unit for the dependency corpus.

The authors 1) do not specify which languages are taken as a model for defining the word, 2) do not define what they mean by "the word as in many languages", and 3) do not specify which languages have an orthography which fails to divide sentences correctly into 'words'. Since they do not make explicit the basis for their assertions, it is impossible to evaluate their claims.

From examples in the paper, however, it is clear that the 'word' that they have in mind for Japanese is the 語 go of school grammar. As we have seen, this does not equate to the word as defined linguistically and is not congruent with the word in other languages. Mori et al thus fail to provide cogent grounds for discarding the bunsetsu.

Low-level parsing procedures

It is possible that the language that uses white space to divide sentences into phrases referred to by Mori et al is Korean. Indeed, Tanaka and Nagata (2013) list another source which provides possible grounds for discarding the bunsetsu: Choi et al. (2012), Korean Treebank Transformation for Parser Training.

This paper deals with mechanical obstacles to parsing the Korean equivalent of the bunsetsu, known as the eojeol (어절). The eojeol is defined as "a word or its variant word-form agglutinated with grammatical affixes". Unlike Japanese, the Korean orthography separates eojeol with white spaces.

The paper exemplifies this with the string 엠머누엘 웅가로가 emanuel ungaro-ga 'Emanuel Ungaro (subject)'. A space in Korean orthography splits this into two parts, emanuel and ungaro-ga, preventing parsing procedures from arriving at the correct form, emanuelungaro-ga (one word).

While Choi et al do not mention it, this problem is not confined to foreign names. The paper Learning from a Neighbor: Adapting a Japanese Parser for Korean through Feature Transfer Learning (Kanayama et al 2014) notes that Korean uses white space to split the expression 여행 가방을 yeohaeng gabang-eul 'travel bag (object)' into two eojeol -- 여행 yeohaeng 'travel' and 가방을 gabang-eul 'bag (object)'. Here it is clear that 여행가방 yeohaeng-gabang 'travel bag' functions as a single unit, and that 을 -eul 'object' correctly attaches to 'travel bag' as a whole. That is, parsing procedures need to arrive at the compound noun yeohaenggabang-eul, not the orthographic form yeohaeng gabang-eul.

Based on low-level parsing issues like those presented above, Choi et al propose dispensing with the eojeol for NLP. Tanaka and Nagata (2013) appear to be implying that the same logic should apply to Japanese.

But Japanese does not have the same problems as Korean since it does not use white spaces to divide vocabulary. The Japanese for Emanuel Ungaro is written エマニュエル・ウンガロ emanyueru.ungaro, divided by a central dot. Since the central dot is largely confined to foreign borrowings, it does not present the parsing problems of a space. emanyueru.ungaro-ga can be correctly parsed as one word plus particle.

The Japanese equivalent to 여행 가방을 yeohaeng gabang-eul is 旅行かばんを ryokō-kaban o 'travel bag (object)', which does not explicitly separate 旅行かばん ryokō kaban 'travel bag' into two words (although such an intepretation is possible). Problems with this kind of eojeol in Korean therefore do not constitute grounds for discarding the bunsetsu in Japanese NLP. This is not to imply that parsing strings of nouns is not an issue for NLP, as noted by Maekawa et al, but Japanese manifestly does not face the same low-level procedural problems faced by Korean.

Arguments of grammar and logic

Some papers raise grammatical and logical objections to the bunsetsu. One of these is Problems for successful bunsetsu based parsing and some solutions (Butler et al 2012a), which is cited at Keyaki Treebank: phrase structure with functional information for Japanese (Butler et al 2015b), one of the references that Tanaka et al 2015 cite.

Unfortunately the title of the paper is misleading; virtually none of the problems raised can be blamed on the bunsetsu.

The first example given is:

私は彼について走った

watashi wa kare ni tsuite hashitta

'I ran following him'私は彼について話した

watashi wa kare ni tsuite hanashita

'I talked about him'The problem here lies with について ni tsuite. The verb つく tsuku has a broad semantic scope, with the very general meaning of 'to attach to'. In the first sentence, it has the specific meaning of 'to follow', and the meaning of について ni tsuite is quite transparently 'following', as interpreted by the normal rules of grammar.

In the second sentence, について ni tsuite is a fixed expression conventionally used to mean 'about, concerning'. This is a lexical issue: the lexicon needs to specify that について ni tsuite can be interpreted as meaning 'about, concerning'. This is a valid candidate for using mwe (mult-word expression) in UD.

This example is similar to the problem of interpreting an English expression like 'with respect to your friend', which could be a literal expression of respect to your friend, or could mean 'with regard to your friend' or 'concerning your friend'. The root of the problem lies not in the grammatical analysis ('preposition + noun + preposition') but in the need to list 'with respect to' as a fixed expression in the lexicon with a customary meaning not totally predictable from its parts.

The second example is:

昨日とった写真がかかっていた

kinō totta shashin ga kakatte ita

'the photo that we took yesterday was hanging'子供が泳いでいる写真がかかっていた

kodomo ga oyoide iru shashin ga kakatte ita